Tag: OEIS

-

Zimin Words and Bifixes

—

by

One of the earliest contributions to the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS) was a family sequences counting the number of words that begin (or don’t begin) with a palindrome: Let \(f_k(n)\) be the number of strings of length \(n\) over a \(k\)-letter alphabet that begin with a nontrivial palindrome” for various values of \(k\).…

-

My Favorite Sequences: A263135

—

by

This is the fourth in my installment of My Favorite Sequences. This post discusses sequence A263135 which counts penny-to-penny connections among \(n\) pennies on the vertices of a hexagonal grid. I published this sequence in October 2015 when I was thinking about hexagonal-grid analogs to the “Not Equal” grid. The square-grid analog of this sequence…

-

My Favorite Sequences: “Not Equal” Grid

—

by

This is the third installment in a recurring series, My Favorite Sequences. This post discusses OEIS sequence A278299, a sequence that took over two years to compute enough terms to add to the OEIS with confidence that it was distinct. This sequence is discussed in Problem #23 of my Open Problems Collection, which asks for…

-

My Favorite Sequences: A261865

—

by

This is the first installment in a new series, “My Favorite Sequences”. In this series, I will write about sequences from the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences that I’ve authored or spent a lot of time thinking about. I’ve been contributing to the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences since I was an undergraduate. In December…

-

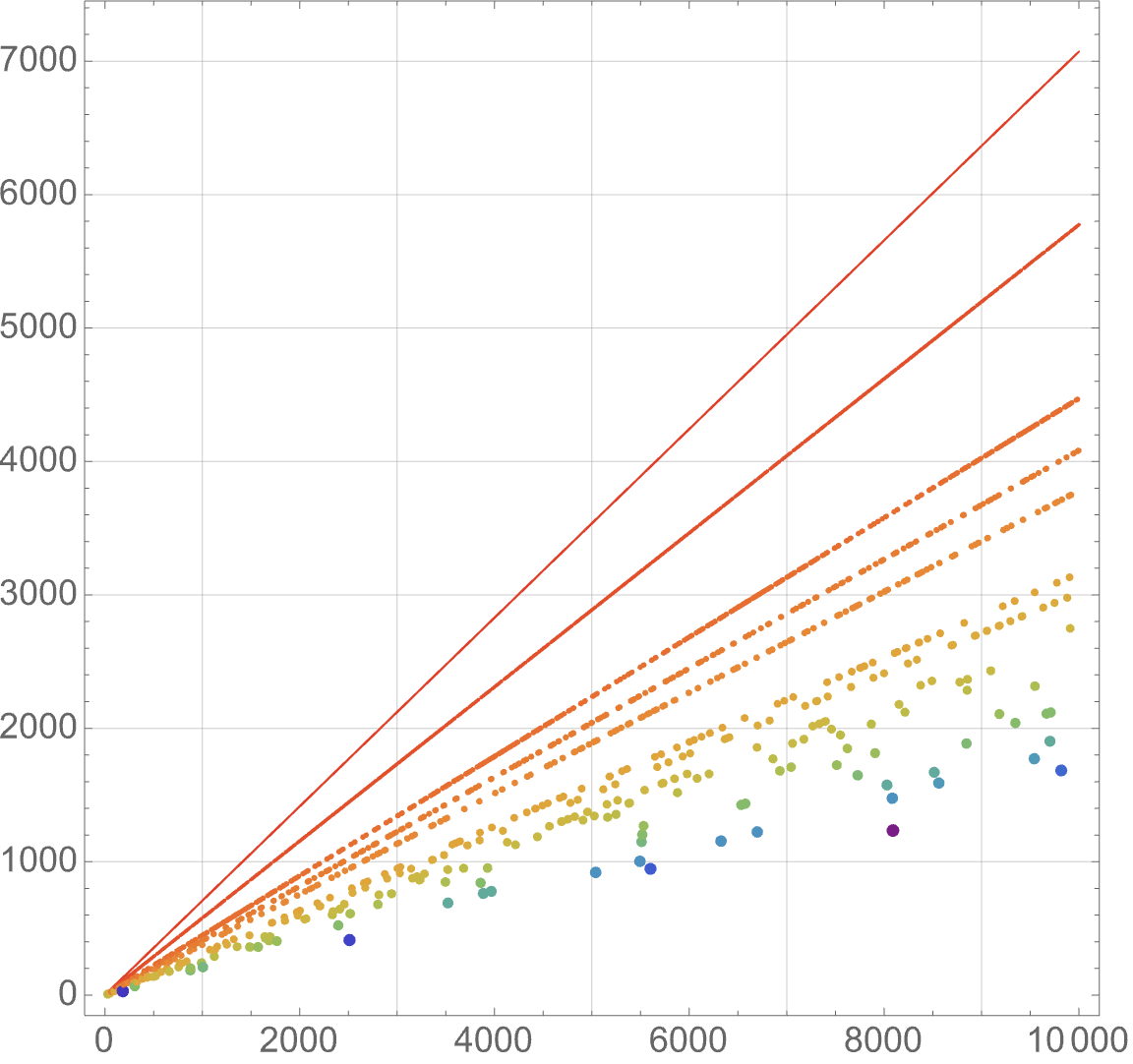

Richard Guy’s Partition Sequence

—

by

Neil Sloane is the founder of the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS). Every year or so, he gives a talk at Rutgers in which he discusses some of his favorite recent sequences. In 2017, he spent some time talking about a 1971 letter that he got from Richard Guy, and some questions that went…

-

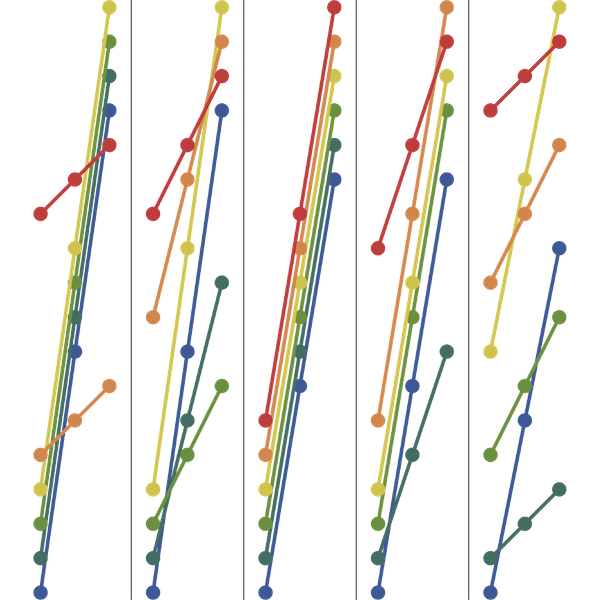

Polytopes with Lattice Coordinates

—

by

Problems 21, 66, and 116 in my Open Problem Collection concern polytopes with lattice coordinates—that is, polygons, polyhedra, or higher-dimensional analogs with vertices the square or triangular grids. (In higher dimensions, I’m most interested in the \(n\)-dimensional integer lattice and the \(n\)-simplex honeycomb). This was largely inspired by one of my favorite mathematical facts: given…

-

Parity Bitmaps from the OEIS

—

by

My friend Alec Jones and I wrote a Python script that takes a two-dimensional sequence in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences and uses it to create a one-bit-per-pixel (1BPP) “parity bitmaps“. The program is simple: it colors a given pixel is black or white depending on whether the corresponding value is even or odd.…